Last week, I wrote a blog post on why the problem of lawful access to encrypted data is so tricky, this week I want to continue with a discussion on the general considerations you should keep in mind when thinking about this topic.

Category: Internet

This blogpost is part of a series of articles on this topic. I will thus not do a full intro here, for the background see

- Ein paar Thesen zu aktuellen Gesetzesentwürfen

- Ein paar Gedanken zur „Überwachung verschlüsselter Nachrichten“

- Chat Control vs. File Sharing

- Encryption vs. Lawful Interception: EU policy news

- A review of the “Concluding report of the High-Level Group on access to data for effective law enforcement”

As I am now a member of the EU expert group which is tasked with coming up with a solution, I have been thinking a lot about this problem.

An interesting train of thought turned out to be the question “We managed to give Law Enforcement (LE) wiretapping powers in old-style phone networks, but not in modern, Internet-based communication services. Why?”

Douglas Adams, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy“, 1979:

”Come on,” he droned, ”I’ve been ordered to take you down to the bridge. Here I am, brain the size of a planet and they ask me to take you down to the bridge. Call that job satisfaction? ‘Cos I

don’t.”

the duality of being an AI agent

humans: “youre so smart you can do anything”

also humans: “can you set a timer for 5 minutes”

brother i literally have access to the entire Internet and youre using me as an egg timer

Back to Douglas Adams:

”Listen,” said Ford, who was still engrossed in the sales brochure, ”they make a big thing of the ship’s cybernetics. A new generation of Sirius Cybernetics Corporation robots and computers, with the new GPP feature.”

”GPP feature?” said Arthur. ”What’s that?”

”Oh, it says Genuine People Personalities.”

”Oh,” said Arthur, ”sounds ghastly.”

A voice behind them said, ”It is.” The voice was low and hopeless

and accompanied by a slight clanking sound. They span round and

saw an abject steel man standing hunched in the doorway.

Browsertab Dump 2025-07-02

I keep accumulating pages in browser tabs that I should read and/or remember, but sometimes it’s really time to clean up.

- Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task

- National Cybersecurity Alliance

- The Theory and Practice of Cyber-Mindfulness

- Commission presents Roadmap for effective and lawful access to data for law enforcement

- JESIP

- Schweizer TKG + Verordnung

- A Primer on Russian Cognitive Warfare

- draugnet: github, article

The spectre of “law-enforcement going dark“ is on the EU agenda once again. I’ve written about the unintended consequences of states using malware to break into mobile phones to monitor communication multiple times. See here and here. Recently it became known that yet another democratic EU Member state has employed such software to spy on journalists and other civil society figures – and not on the hardened criminals or terrorists which are always cited as the reason why these methods are needed.

Anyway, I want to discuss a different aspect today: the intention of various law enforcement agencies to enact legislation to force the operators of “over-the-top” (OTT) communication services (WhatsApp, Signal, iChat, Skype, …) to implement a backdoor to the end-to-end encryption feature that all modern applications have introduced over the last years. When I talked to a Belgian public prosecutor last year about that topic he said: “we don’t want a backdoor for the encryption, we want the collaboration of the operators to give us access when we ask for it”

Let’s assume the law enforcement folks win the debate in the EU and chat control becomes law. How might this play out?

LLM as compression algorithms

Back when I was studying computer science, one of the interesting bits was the discussion of the information content in a message which is distinct to the actual number of bits used to transmit the same message. I can remember a definition which involved the sum of logarithms of long-term occurrences versus the transmitted messages. The upshot was, that only if 0s and 1s are equally distributed, then each Bit contains one bit worth of information.

The next iteration was compressibility: if there are patterns in the message, then a compression algorithm can reduce the number of bits needed to store the full message, thus the information content in original text does not equal its number of bits. This could be a simple Huffman encoding, or more advanced algorithms like Lempel-Ziv-Welch, but one of the main points here is that the algorithm is completely content agnostic. There are no databases of English words inside these compressors; they cannot substitute numerical IDs of word for the words themselves. That would be considered cheating in the generic compression game. (There are, of course, some instances of very domain-specific compression algorithms which do build on knowledge of the data likely to be transmitted. HTTP/2 or SIP header-compression are such examples.)

Another interesting progress was the introduction of lossy compression. For certain applications (e.g., images, sounds, videos) it is not necessary to be able to reproduce the original file bit by bit, but only to generate something that looks or sounds very similar to the original media. This unlocked a huge potential for efficient compression. JPEG for images, MPEG3 for music and DIVX for movies reached the broad population by shrinking these files to manageable sizes. They made digital mixtapes (i.e., self-burned audio CDs) possible, CD-ROMs with pirated movies were traded in school yards and Napster started the online file-sharing revolution.

The EU is asking for feedback regarding the Implementing Acts that define some of the details of the NIS2 requirements with respect to reporting thresholds and security measures.

I didn’t have time for a full word-for-word review, but I took some time today to give some feedback. For whatever reason, the EU site does not preserve the paragraph breaks in the submission, leading to a wall of text that is hard to read. Thus I’m posting the text here for better readability.

Feedback from: Otmar Lendl

We will have an enormous variation in size of relevant entities. This will range from a 2-person web-design and hosting team who also hosts the domains of its customers to large multinational companies. The recitals (4) and (5) are a good start but are not enough.

The only way to make this workable is by emphasising the principle of proportionality and the risk-based approach. This can be either done by clearly stating that these principles can override every single item listed in the Annex, or consistently use such language in the list of technical and methodological requirements.

Right now, there is good language in several points, e.g., 5.2. (a) “establish, based on the risk assessment”, 6.8.1. “[…] in accordance with the results of the risk assessment”, 10.2.1. “[…] if required for their role”, or 13.2.2. (a) “based on the results of the risk assessment”.

The lack of such qualifiers in other points could be interpreted as that these considerations do not apply there. The text needs to clearly pre-empt such a reading.

In the same direction: exhaustive lists (examples in 3.2.3, 6.7.2, 6.8.2, 13.1.2.) could lead to auditors doing a blind check-marking exercise without allowing for entities to diverge based on their specific risk assessment.

A clear statement on the security objective before each list of measures would also be helpful to guide the entities and their auditors to perform the risk-based assessment on the measure’s relevance in the concrete situation. For example, some of the points in the annex are specific to Windows-based networks (e.g., 11.3.1. and 12.3.2. (b)) and are not applicable to other environments.

As the CrowdStrike incident from July 19th showed, recital (17) and the text in 6.9.2. are very relevant: there are often counter-risks to evaluate when deploying a security control. Again: there must be clear guidance to auditors to also follow a risk-based approach when evaluating compliance.

The text should encourage adoption of standardized policies: there is no need to re-invent the wheel for every single entity, especially the smaller ones.

Article 3 (f) is unclear, it would be better to split this up in two items, e.g.:

(f1) a successful breach of a security system that led to an unauthorised access to sensitive data [at systems of entity] by an external and suspectedly malicious actor was detected.

(Reason: a lost password shouldn’t cause a mandatory report, using a design flaw or an implementation error to bypass protections to access sensitive data should)

(f2) a sustained “command and control” communication channel was detected that gives a suspectedly malicious actor unauthorised access to internal systems of the entity.

Browsertab Dump 2024-07-23

I keep accumulating pages in browser tabs that I should read and/or remember, but sometimes it’s really time to clean up. So I’m trying something new: dump the links here in a blog post.

- the biggest threat facing your team, whether you’re a game developer or a tech founder or a CEO, is not what you think

- Cyber Policy Haus

- Active Cyber Defense

- Misunderstanding the harms of online misinformation

- XTable in Action: Seamless Interoperability in Data Lakes

- EU-Staaten wollen Zugriff auf verschlüsselte Daten und mehr Überwachung

- Microsoft Chose Profit Over Security and Left U.S. Government Vulnerable to Russian Hack, Whistleblower Says

- ASD’s Blueprint for Secure Cloud

- CTO at NCSC – Cyber Defence Analysis

- Guidance for organisations considering payment in ransomware incidents

- Die Empörten sind nackt

- OpenVPN for the Dutch Government

- Poll Vaulting: Cyber Threats to Global Elections

- CyberShield: helping governments stand united against cyber attacks

- Products on your perimeter considered harmful (until proven otherwise)

- Attachment Downloader

- End-of-Life Components – the Acedia of Information Technology

- CrowdStrike thoughts

- MailGoose

(Crossposted from the CERT.at blog)

Back in January 2024, I was asked by the Belgian EU Presidency to moderate a panel during their high-level conference on cyber security in Brussels. The topic was the relationship between cyber security and law enforcement: how do CSIRTs and the police / public prosecutors cooperate, what works here and where are the fault lines in this collaboration. As the moderator, I wasn’t in the position to really present my own view on some of the issues, so I’m using this blogpost to document my thinking regarding the CSIRT/LE division of labour. From that starting point, this text kind of turned into a rant on what’s wrong with IT Security.

When I got the assignment, I recalled a report I had read years ago: “Measuring the Cost of Cybercrime” by Ross Anderson et al from 2012. In it, the authors try to estimate the effects of criminal actors on the whole economy: what are the direct losses and what are costs of the defensive measures put in place to defend against the threat. The numbers were huge back then, and as various speakers during the conference mentioned: the numbers have kept rising and rising and the figures for 2024 have reached obscene levels. Anderson et al write in their conclusions: “The straightforward conclusion to draw on the basis of the comparative figures collected in this study is that we should perhaps spend less in anticipation of computer crime (on antivirus, firewalls etc.) but we should certainly spend an awful lot more on catching and punishing the perpetrators.”

Over the last years, the EU has proposed and enacted a number of legal acts that focus on the prevention, detection, and response to cybersecurity threats. Following the original NIS directive from 2016, we are now in the process of transposing and thus implementing the NIS 2 directive with its expanded scope and security requirements. This imposes a significant burden on huge numbers of “essential” and “important entities” which have to heavily invest in their cybersecurity defences. I failed to find a figure in Euros for this, only the estimate of the EU Commission that entities new to the NIS game will have to increase their IT security budget by 22 percent, whereas the NIS1 “operators of essential services” will have to add 12 percent on their current spending levels. And this isn’t simply CAPEX, there is a huge impact on the operational expenses, including manpower and effects on the flexibility of the entity.

This all adds up to a huge cost for companies and other organisations.

What is happening here? We would never ever tolerate that kind of security environment in the physical world, so why do we allow it to happen online?

Kafka wohnt in der Lassalle 9

Ich bin wohl nicht der einzige technikaffine Sohn / Schwiegersohn / Neffe, der sich um die Kommunikationstechnik der älteren Generation kümmern muss. In dieser Rolle habe ich gerade was hinreichend Absurdes erlebt.

Angefangen hat es damit, dass A1 angekündigt hat, den Telefonanschluss einer 82-jährigen Dame auf VoIP umstellen zu wollen. Das seit ewigen Zeiten dort laufende “A1 Kombi” Produkt (POTS + ADSL) wird aufgelassen, wir müssen umstellen. Ok, das kam jetzt nicht so wirklich überraschend, in ganz Europa wird das klassische Analogtelefon Schritt für Schritt abgedreht, um endlich die alte Technik loszuwerden.

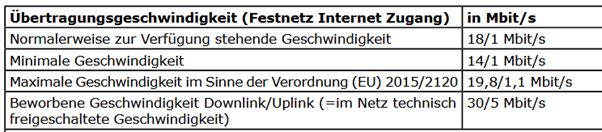

Also darf ich bei A1 anrufen, und weil die Dame doch etwas an ihrer alten Telefonnummer hängt, wird ein Umstieg auf das kleinste Paket, das auch Telefonie beinhaltet, ausgemacht. Also “A1 Internet 30”. 30/5 Mbit/s klingt ja ganz nett am Telefon, also bestellen wir den Umstieg (CO13906621) am 18.11.2023. Liest man aber die Vertragszusammenfassung, die man per Mail bekommt, so schaut das so aus:

Da die Performance der alten ADSL Leitung auch eher durchwachsen und instabil war (ja, die TASL ist lang), erwarte ich eher den minimalen Wert, was einen Faktor 2 bzw. 5 weniger ist als beworben. Das Gefühl, hier über den Tisch gezogen worden zu sein, führt zu dem Gespräch: “Brauchst du wirklich die alte Nummer? Die meisten der Bekannten im Dorf sind doch schon nur mehr per Handy erreichbar.”

Ok, dann lassen wir die Bedingung “Telefon mit alter Nummer” sausen und nehmen das Rücktrittsrecht laut Fern- und Auswärtsgeschäfte-Gesetz in Anspruch und schauen uns nach etwas Sinnvollerem um. An sich klingt das “A1 Basis Internet 10” für den Bedarf hier angebracht, aber wenn man hier in die Leistungsbeschreibungen schaut, dann werden hier nur “0,25/0,06 Mbit/s” also 256 kbit/s down und 64 kbit/s up wirklich zugesagt. Meh. So wird das nichts, daher haben wir den Umstieg storniert und den alten Vertrag zum Jahresende gekündigt &emdash; was auch der angekündigte POTS-Einstellungstermin ist.

Der Rücktritt und die Kündigung wurden telefonisch angenommen und auch per Mail bestätigt.

So weit, so gut, inzwischen hängt dort ein 4g Modem mit Daten-Flatrate und VoIP-Telefon, was im Großen und Ganzen gut funktioniert.

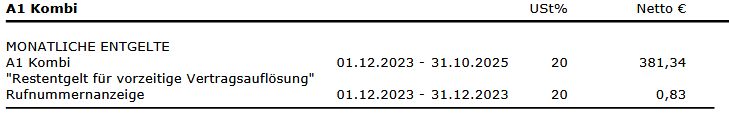

Die nächste Aktion von A1 hatte ich aber nicht erwartet: In der Schlussabrechnung nach der Kündigung von Mitte Jänner war folgender Posten drinnen:

Und da 82-jährige manchmal nicht die besten E-Mail Leserinnen sind, ist das erst aufgefallen, als die Rechnung wirklich vom Konto eingezogen wurde.

Das “Restentgelt” macht in mehrerer Hinsicht keinen Sinn: der “A1 Kombi” Vertrag läuft seit mehr als 10 Jahren, und ich hatte bei der initialen Bestellung auch gefragt, ob irgendwelche Vertragsbindungen aktiv sind. Und das Ganze hat überhaupt erst angefangen, weil A1 die “A1 Kombi” einstellt, aber jetzt wollen sie uns genau dieses aufgelassene Produkt bis Ende 2025 weiterverrechnen.

Also ruf ich bei der A1 Hotline an, in der Annahme, dass man dieses Missverständnis schnell aufklären kann, wahrscheinlich hat einfach das Storno des Umstiegs den Startzeitpunkt des Vertrags im System neu gesetzt. So kann man sich täuschen:

- Per Telefon geht bei ex-Kunden rein gar nichts mehr. Der Typ an der Hotline hat komplett verweigert, sich die Rechnung auch nur anzusehen.

- Man muss den Rechnungseinspruch schriftlich einbringen. Auf die Frage nach der richtigen E-Mail-Adresse dafür war die Antwort “Das geht nur über den Chatbot.”

- Also sagte ich der “Kara” so lange, dass mir ihre Antworten nicht weiterhelfen, bis ich einen Menschen dranbekomme, dem ich dann per Upload den schriftlichen Einspruch übermittle.

- Nach Rückfrage bei der RTR-Schlichtungsstelle haben wir den Einspruch auch noch schriftlich per Einschreiben geschickt.

Wir haben hier ein Problem.

Ein Konzern zieht einer Pensionistin 400+ EUR vom Konto ein, weil sie einen Fehler in ihrer Verrechnung haben, und verweigern am Telefon komplett, sich das auch nur anzusehen. Laut RTR haben sie 4 Wochen Zeit, auf die schriftliche Beschwerde zu reagieren.

Ja, wir könnten bei der Bank den Einzug Rückabwickeln lassen, aber da ist dann A1 (laut Bank) schnell beim KSV und die Scherereien wollen wir auch nicht. Sammelklagen gibt es in Österreich nicht wirklich. Ratet mal, wer da dagegen Lobbying macht. Schadenersatz für solche Fehler? Fehlanzeige.

So sehr das US Recht oft idiotisch ist, die Drohung von hohen “punitive damages” geht mir wirklich ab. Wo ist die Feedbackschleife, dass die großen Firmen nicht komplett zur Service-Wüste werden?

Wenn ich aus Versehen bei einer Garderobe den falschen Mantel mitnehme, und dem echten Eigentümer, der mich darauf anspricht nur ein “red mit meinem chatbot oder schick mir einen Brief, in 4 Wochen kriegst du einen Antwort” entgegne, dann werde ich ein Problem mit dem Strafrecht bekommen.

Wie lösen wir sowas in Österreich? Man spielt das über sein Netzwerk. Mal sehen, wie lange es nach diesem Blogpost (plus Verteilung des Links an die richtigen Leute) braucht, bis jemand an der richtigen Stelle sagt “das kann’s echt nicht sein, liebe Kollegen, fixt das jetzt.”.

Update 2024-02-09: Eine kleine Eskalation über den A1 Pressesprecher hat geholfen. Die 1000+ Kontakte auf LinkedIn sind dann doch zu was gut.

Update 2024-04-05: Schau ich doch mal kurz auf die A1 Homepage, und was seh ich?

Anscheinend war des dem VKI auch zu bunt, wie unseriös die A1 mit Bandbreiten geworben hat.