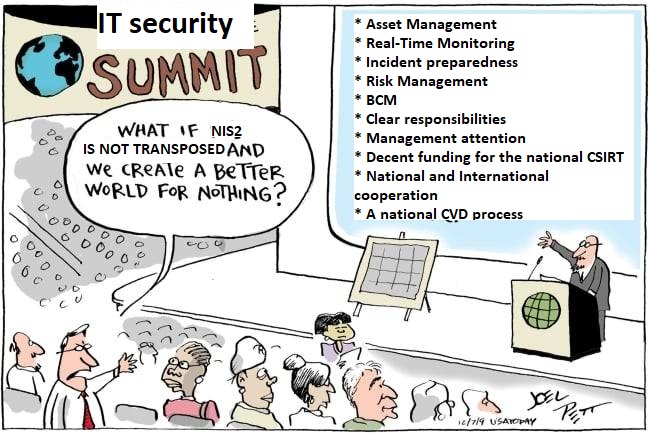

Last week I was invited to provide some input to a tabletop exercise for city-level crisis managers on cyber security risks and the role of CSIRTs. The organizers brought a color-coded threat-level sheet (based on the CISA Alert Levels) to the discussion and asked whether we also do color-coded alerts in Austria and what I think of these systems.

My answer was negative on both questions, and I think it might be useful if I explain my rationale here. The first was rather obvious and easy to explain, the second one needed a bit of thinking to be sure why my initial intuition to the document was so negative.

Escalation Ratchet

The first problem with color-coded threat levels is their tendency to be a one-way escalation ratchet: easy to escalate, but hard to de-escalate. I’ve been hit by that mechanism before during a real-world incident and that led me to be wary of that effect. Basically, the person who raises the alert takes very little risk: if something bad happens, she did the right thing, and if the danger doesn’t materialize, then “better safe than sorry” is proclaimed, and everyone is happy, nevertheless. In other words, raising the threat level is a safe decision.

On the other hand, lowering the threat level is an inherently risky decision: If nothing bad happens afterwards, there might be some “thank you” notes, but if the threat materializes, then the blame falls squarely on the shoulders of the person who gave the signal that the danger was over. Thus, in a CYA-dominated environment like public service, it is not a good career move to greenlight a de-escalation.

We’ve seen this process play out in the non-cyber world over the last years, examples include

- Terror threat level after 9/11

- Border controls in the Schengen zone after the migration wave of 2015

- Coming down from the pandemic emergency

That’s why I’ve been always pushing for clear de-escalation rules to be in place whenever we do raise the alarm level.

Cost of escalation

For threat levels to make sense, any level above “green” need to have a clear indication what the recipient of the warnings should be doing at this threat level. In the example I saw, there was a lot of “Identify and patch vulnerable systems”. Well, Doh! This is what you should be doing at level green, too.

Thus, relevant guidance at higher level needs to be more than “protect your systems and prepare for attacks”. That’s a standing order for anyone doing IT operation, this is useless advice as escalation. What people need to know is what costs they should be willing to pay for a better preparation against incidents.

This could be a simple thing like “We expect a patch for a relevant system to be released out of our office-hours, we need to have a team on standby to react as quickly as possible, and we’ve willing to pay for the overtime work to have the patch deployed ASAP.”. Or the advice could be “You need to patch this outside your regular patching cadence, plan for a business disruption and/or night shifts for the IT people.” At the extreme end, it might even be “we’re taking service X out of production, the changes to the risk equation mean that its benefits can’t justify the increased risks anymore.”.

To summarize: if there were no hard costs to a preventative security measure, then you should have implemented them a long time ago, regardless of any threat level board.

Counterpoint

There is definitely value in categorizing a specific incident or vulnerability in some sort of threat level scheme: A particularly bad patch day, or some out-of-band patch release by an important vendor certainly is a good reason that the response to the threat should also be more than business-as-usual.

But a generic threat level increase without concrete vulnerabilities listed or TTPs to guard against? That’s just a fancy way of saying “be afraid” and there is little benefit in that.

Postscript: Just after posting this article, I stumbled on a fediverse post making almost the same argument, just with April 1st vs. the everyday flood of misinformation.