Rebooting the Blog with a clean WordPress install and finally no more encoding issues.

WordPress still isn’t really doing what I want it to do.

Rebooting the Blog with a clean WordPress install and finally no more encoding issues.

WordPress still isn’t really doing what I want it to do.

(Crossposted from the CERT.at blog.)

As I’ve written here, the EU unveiled a roadmap for addressing the encryption woes of law enforcement agencies in June 2025. As a preparation for this push, a “High-Level Group on access to data for effective law enforcement” has summarized the problems for law enforcement and developed a list of recommendations.

(Side note: While the EU Chat Control proposal is making headlines these days and has ben defeated – halleluja -, the HLG report is dealing with a larger topic. I will not comment on the Chat Control/CSAM issues here at all.)

I’ve read this this report and its conclusions, and it is certainly a well-argued document, but strictly from a law enforcement perspective. Some points are pretty un-controversial (shared training and tooling), others are pretty spicy. In a lot of cases, it hedges by using language similar to the one used by the Commission:

In 2026, the Commission will present a Technology Roadmap on encryption to identify and evaluate solutions that enable lawful access to encrypted data by law enforcement, while safeguarding cybersecurity and fundamental rights.

They are not presenting concrete solutions; they are hoping that there is a magic bullet which will fulfill all the requirements. Let’s see what this expert group will come up with.

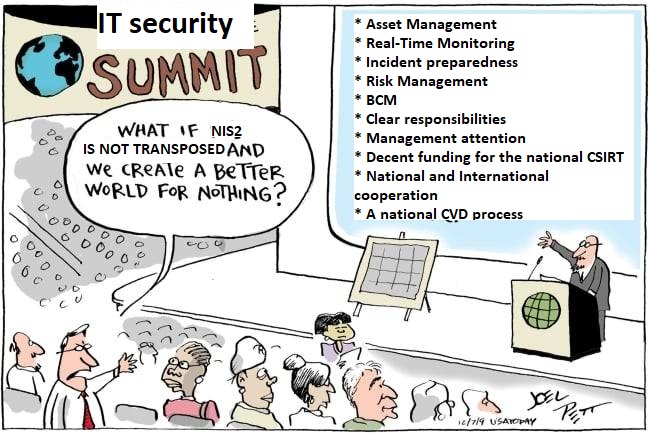

We still don’t have a NIS2 law in Austria. We’re now more than a year late. As I just saw Süleyman’s post on LinkedIn I finally did the quick photoshop job I planned to do for a long time.

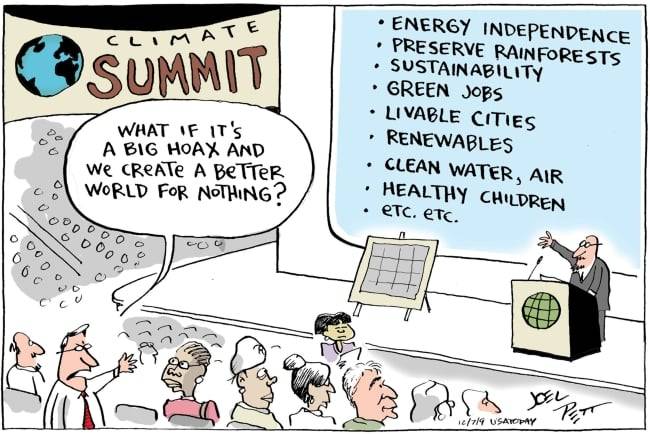

Original:

NIS2 Version:

(Yes, this is a gross oversimplification. For the public administration side, we really need the NIS2 law, but for private companies who will be forced to conform to security standards: what’s holding you back from implementing them right now?)

I keep accumulating pages in browser tabs that I should read and/or remember, but sometimes it’s really time to clean up.

The spectre of “law-enforcement going dark“ is on the EU agenda once again. I’ve written about the unintended consequences of states using malware to break into mobile phones to monitor communication multiple times. See here and here. Recently it became known that yet another democratic EU Member state has employed such software to spy on journalists and other civil society figures – and not on the hardened criminals or terrorists which are always cited as the reason why these methods are needed.

Anyway, I want to discuss a different aspect today: the intention of various law enforcement agencies to enact legislation to force the operators of “over-the-top” (OTT) communication services (WhatsApp, Signal, iChat, Skype, …) to implement a backdoor to the end-to-end encryption feature that all modern applications have introduced over the last years. When I talked to a Belgian public prosecutor last year about that topic he said: “we don’t want a backdoor for the encryption, we want the collaboration of the operators to give us access when we ask for it”

Let’s assume the law enforcement folks win the debate in the EU and chat control becomes law. How might this play out?

Back when I was studying computer science, one of the interesting bits was the discussion of the information content in a message which is distinct to the actual number of bits used to transmit the same message. I can remember a definition which involved the sum of logarithms of long-term occurrences versus the transmitted messages. The upshot was, that only if 0s and 1s are equally distributed, then each Bit contains one bit worth of information.

The next iteration was compressibility: if there are patterns in the message, then a compression algorithm can reduce the number of bits needed to store the full message, thus the information content in original text does not equal its number of bits. This could be a simple Huffman encoding, or more advanced algorithms like Lempel-Ziv-Welch, but one of the main points here is that the algorithm is completely content agnostic. There are no databases of English words inside these compressors; they cannot substitute numerical IDs of word for the words themselves. That would be considered cheating in the generic compression game. (There are, of course, some instances of very domain-specific compression algorithms which do build on knowledge of the data likely to be transmitted. HTTP/2 or SIP header-compression are such examples.)

Another interesting progress was the introduction of lossy compression. For certain applications (e.g., images, sounds, videos) it is not necessary to be able to reproduce the original file bit by bit, but only to generate something that looks or sounds very similar to the original media. This unlocked a huge potential for efficient compression. JPEG for images, MPEG3 for music and DIVX for movies reached the broad population by shrinking these files to manageable sizes. They made digital mixtapes (i.e., self-burned audio CDs) possible, CD-ROMs with pirated movies were traded in school yards and Napster started the online file-sharing revolution.

The EU is asking for feedback regarding the Implementing Acts that define some of the details of the NIS2 requirements with respect to reporting thresholds and security measures.

I didn’t have time for a full word-for-word review, but I took some time today to give some feedback. For whatever reason, the EU site does not preserve the paragraph breaks in the submission, leading to a wall of text that is hard to read. Thus I’m posting the text here for better readability.

We will have an enormous variation in size of relevant entities. This will range from a 2-person web-design and hosting team who also hosts the domains of its customers to large multinational companies. The recitals (4) and (5) are a good start but are not enough.

The only way to make this workable is by emphasising the principle of proportionality and the risk-based approach. This can be either done by clearly stating that these principles can override every single item listed in the Annex, or consistently use such language in the list of technical and methodological requirements.

Right now, there is good language in several points, e.g., 5.2. (a) “establish, based on the risk assessment”, 6.8.1. “[…] in accordance with the results of the risk assessment”, 10.2.1. “[…] if required for their role”, or 13.2.2. (a) “based on the results of the risk assessment”.

The lack of such qualifiers in other points could be interpreted as that these considerations do not apply there. The text needs to clearly pre-empt such a reading.

In the same direction: exhaustive lists (examples in 3.2.3, 6.7.2, 6.8.2, 13.1.2.) could lead to auditors doing a blind check-marking exercise without allowing for entities to diverge based on their specific risk assessment.

A clear statement on the security objective before each list of measures would also be helpful to guide the entities and their auditors to perform the risk-based assessment on the measure’s relevance in the concrete situation. For example, some of the points in the annex are specific to Windows-based networks (e.g., 11.3.1. and 12.3.2. (b)) and are not applicable to other environments.

As the CrowdStrike incident from July 19th showed, recital (17) and the text in 6.9.2. are very relevant: there are often counter-risks to evaluate when deploying a security control. Again: there must be clear guidance to auditors to also follow a risk-based approach when evaluating compliance.

The text should encourage adoption of standardized policies: there is no need to re-invent the wheel for every single entity, especially the smaller ones.

Article 3 (f) is unclear, it would be better to split this up in two items, e.g.:

(f1) a successful breach of a security system that led to an unauthorised access to sensitive data [at systems of entity] by an external and suspectedly malicious actor was detected.

(Reason: a lost password shouldn’t cause a mandatory report, using a design flaw or an implementation error to bypass protections to access sensitive data should)

(f2) a sustained “command and control” communication channel was detected that gives a suspectedly malicious actor unauthorised access to internal systems of the entity.

I keep accumulating pages in browser tabs that I should read and/or remember, but sometimes it’s really time to clean up. So I’m trying something new: dump the links here in a blog post.

At CERT.at, we recently changed the way we send out bulk email notifications with RT: All Correspondence from the Automation user will have a different From: address compared to constituency interactions done manually by one of our analysts.

How did I implement this?

In the end, it was just a one-liner in the right spot. Our “Correspondence”-Template looks like this now:

RT-Attach-Message: yes

Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit{($Transaction->CreatorObj->Name eq 'intelmq') ? "\nFrom: noreply\@example.at" : ""}

{$Transaction->Content()}

The “Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit” was needed because of the CipherMail instance, without it we could get strange MIME encoding errors.

(Crossposted from the CERT.at blog)

Back in January 2024, I was asked by the Belgian EU Presidency to moderate a panel during their high-level conference on cyber security in Brussels. The topic was the relationship between cyber security and law enforcement: how do CSIRTs and the police / public prosecutors cooperate, what works here and where are the fault lines in this collaboration. As the moderator, I wasn’t in the position to really present my own view on some of the issues, so I’m using this blogpost to document my thinking regarding the CSIRT/LE division of labour. From that starting point, this text kind of turned into a rant on what’s wrong with IT Security.

When I got the assignment, I recalled a report I had read years ago: “Measuring the Cost of Cybercrime” by Ross Anderson et al from 2012. In it, the authors try to estimate the effects of criminal actors on the whole economy: what are the direct losses and what are costs of the defensive measures put in place to defend against the threat. The numbers were huge back then, and as various speakers during the conference mentioned: the numbers have kept rising and rising and the figures for 2024 have reached obscene levels. Anderson et al write in their conclusions: “The straightforward conclusion to draw on the basis of the comparative figures collected in this study is that we should perhaps spend less in anticipation of computer crime (on antivirus, firewalls etc.) but we should certainly spend an awful lot more on catching and punishing the perpetrators.”

Over the last years, the EU has proposed and enacted a number of legal acts that focus on the prevention, detection, and response to cybersecurity threats. Following the original NIS directive from 2016, we are now in the process of transposing and thus implementing the NIS 2 directive with its expanded scope and security requirements. This imposes a significant burden on huge numbers of “essential” and “important entities” which have to heavily invest in their cybersecurity defences. I failed to find a figure in Euros for this, only the estimate of the EU Commission that entities new to the NIS game will have to increase their IT security budget by 22 percent, whereas the NIS1 “operators of essential services” will have to add 12 percent on their current spending levels. And this isn’t simply CAPEX, there is a huge impact on the operational expenses, including manpower and effects on the flexibility of the entity.

This all adds up to a huge cost for companies and other organisations.

What is happening here? We would never ever tolerate that kind of security environment in the physical world, so why do we allow it to happen online?